Current situation >> Critical thinking

main findings:

Substantial differences exist in the extent to which different programmes support us as students to develop critical mind-sets

Textbooks account for more than half of the teaching materials; these often provide students with a conflict-free and smoothed idea of the current thinking

Most universities do have at least one course offering tools for critical thinking

When it comes to helping us to develop a critical mind, the aggregate picture shows a somewhat more positive image than the other three pillars discussed. Curricula on average pay considerable attention to topics as ethics, economic methodology and philosophy of science, tools that help them to develop a critical mind-set. This should be valued positively. However, such courses teach critical thinking in the abstract. We would argue that the near monopoly of the neoclassical approach undermines the possibility of developing a critical mind, because it doesn’t give us as students the opportunity to develop independent judgements about which approaches are most useful in particular circumstances. Thus, critical thinking as directly applied to the subject matter is not facilitated; it remains an abstract notion.

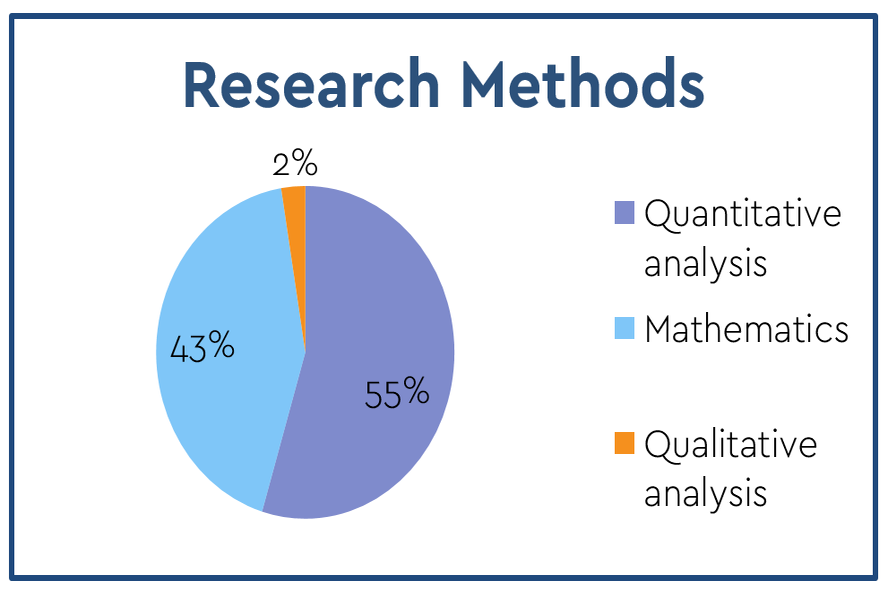

However, the teaching methods are often not suitable for the development of a critical mind-set. More than half of the teaching materials used are textbooks, which generally present theory in the form of a canon, separated from any surrounding discussion or reflection. Testing is increasingly done through multiple choice. Such didactic techniques tend to crowd out discussion, argumentation and development of critical thought, replacing them with the spoon-feeding of ideas and right/wrong testing methods. This is a consequence of the ever higher time pressure on academics, caused by growing student numbers and publication demands. But it does not make for critical, independent student minds.

Why does this matter?

We believe that at the time of graduation, students like us must be able to critically reflect on their own work, that of others, and real-world developments. Developing a critical attitude should therefore be encouraged in curricula.

The abstract, quantitative, monistic thinking with which we are imbued is seldom countered by an invitation to criticize, to question and to look for alternative ideas. In most programs, we do get a course on the philosophy of science, or on economic methodology. But the questions and criticisms provoked by such courses are all too rarely addressed or even acknowledged in the rest of our classes.

“It suggests (...) a readiness to find our surroundings strange and singular; a certain relentlessness in ridding ourselves of our familiarities and looking at things otherwise; a passion for seizing what is happening now and what is passing away; a lack of respect for traditional hierarchies of the important and the essential”

We believe that courses on ‘critical thinking’ generally do not suffice to train students to be critical. Rather, teachers can set an example for us when it comes to developing a critical mind-set, whether they are professors, readers or junior lecturers. They have to show what it means to approach a topic critically; they have to confront us as students with their own arguments, they have to reveal assumptions that are made, they have to raise alternatives or play devil’s advocate to increase the scope and depth of classroom discussions. They have to show that studying and researching is a highly reflective activity. It is then up to the us as students to follow the example that is set. Of course, this does require that teachers are allocated sufficient time to prepare and teach courses. Currently, this is often not the case.

This is also reflected in the didactic methods that are used in a program. Didactic methods are generally not seen as something relevant to the knowledge that is taken in. But an academic education is not just about learning by heart. It is about learning to think, to probe, to argue and to reflect. In fact, it matters very much whether we as students write essays or answer multiple-choice questions. It makes a large difference whether we have to successfully reproduce mathematical equations, or have to defend the position they take through a debate. Therefore, this sub-question also takes didactic methods into account.

Additionally, for developing a critical mind-set, it will help to make us as students familiar with tools to engage in debates in a critical way. Since the critical attitude is about questioning the assumptions of oneself and the other, courses that specifically provide us with tools to reveal assumptions are important. Insights from philosophy of science encourage critical thinking in an economics degree.