Introduction and motivation

Over the seven months from October 2023 to May 2024, the Centre for Economy Studies has compiled a report on the state of undergraduate economics education at universities on the island of Ireland. We have done so with three aims in mind:

To provide academics in Ireland with a summary of the content currently covered in the undergraduate economics curricula.

To spark a discussion about where there are opportunities for improvement in economics education.

To identify examples of best practice in economics education in Ireland that can serve as inspiration for educators globally.

We’ve spoken to dozens of academics across Ireland in the process of making this report, and we hope that this is just the starting point for ongoing conversations about economics education and teaching. We do not intend for this report to be the final word, as there is always space for further collaboration and improvement. We would also note that our analysis is not perfect; we have done our best with the materials available to us, but without observing every class for every module in every programme, there will always be details that we might misunderstand or misrepresent. We have minimised this risk by deliberately restricting our analysis to what is most easily observable through module descriptions and interviews, and by providing an overview of what is taught rather than an exhaustive list.

This is an independent report, it was not commissioned or approved by any university. This report has been funded by Dezernat Zukunft.

How we collected our data, what is included in the report, and what isn’t

The overarching framework for this report is derived from our previous study on undergraduate economics education in the Netherlands, spearheaded by Sam de Muijnck and Joris Tieleman. Jamie Barker and Kristin Dilani Nadarajah have further refined and adapted this framework for the current report. Jamie serves as the lead author, while Kristin Dilani has contributed to writing and editing, as well as taking the lead on the visual design. Sam and Joris have also contributed to the writing process and provided the original framework.

This report investigates the content of undergraduate economics programmes across a broad range of categories. These categories have been chosen to reflect both the current mainstream of economics education, and the building blocks of what we hope will be the future of economics education, largely building on the Economy Studies book. Our categories cover allocation mechanisms, schools of thought, specific economies and sectors, empirical tools, societal challenges, and contributions to economics from other disciplines and subdisciplines. The main gap in this framework is skills development – not because we do not value skills such as critical thinking, communication or collaboration, but because we felt that they would be too difficult to measure from the outside. Most departments embed skills development across all their modules rather than devoting specific modules to the task – although there does seem to be a trend towards introducing skills-specific modules in recent years. You can read our descriptions of each category and subcategory here: Category Descriptions.pdf

The quality of the teaching on each programme is also outside of the scope of this report, as this would require intruding into classrooms to observe classes. In summary, this report examines what is taught and not how it is taught.

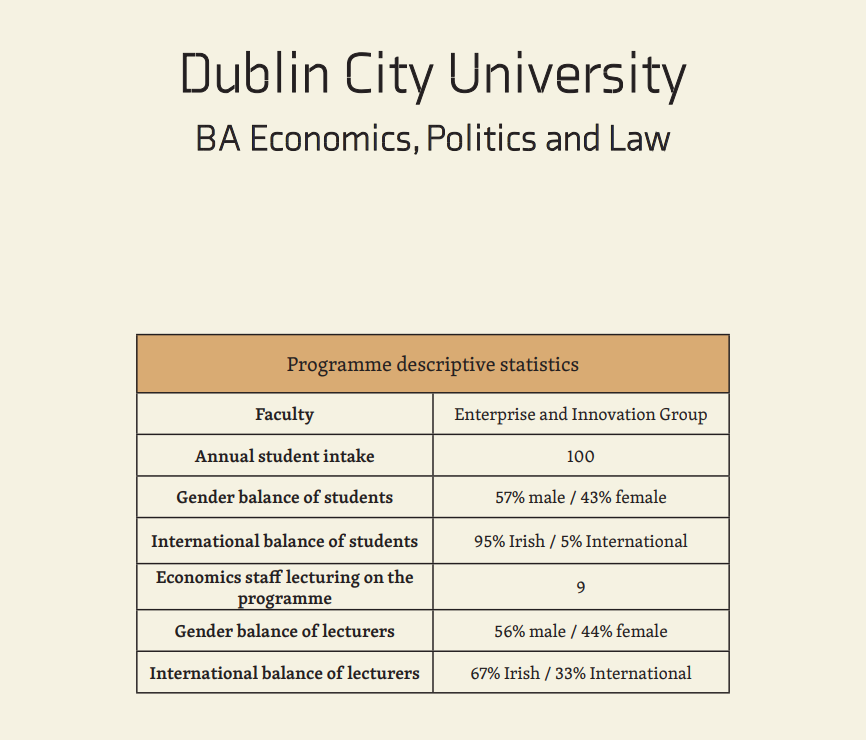

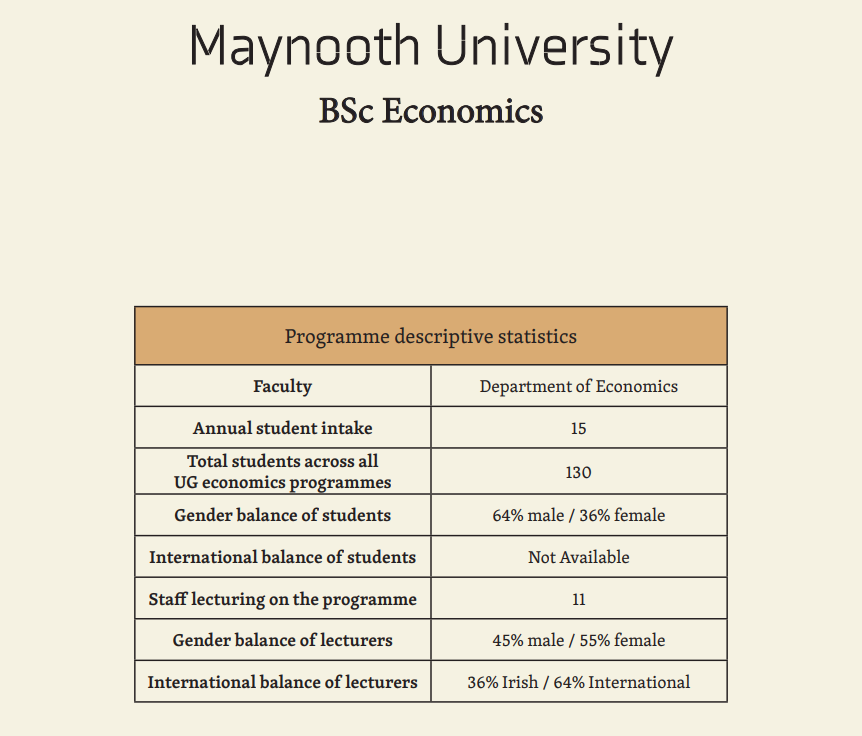

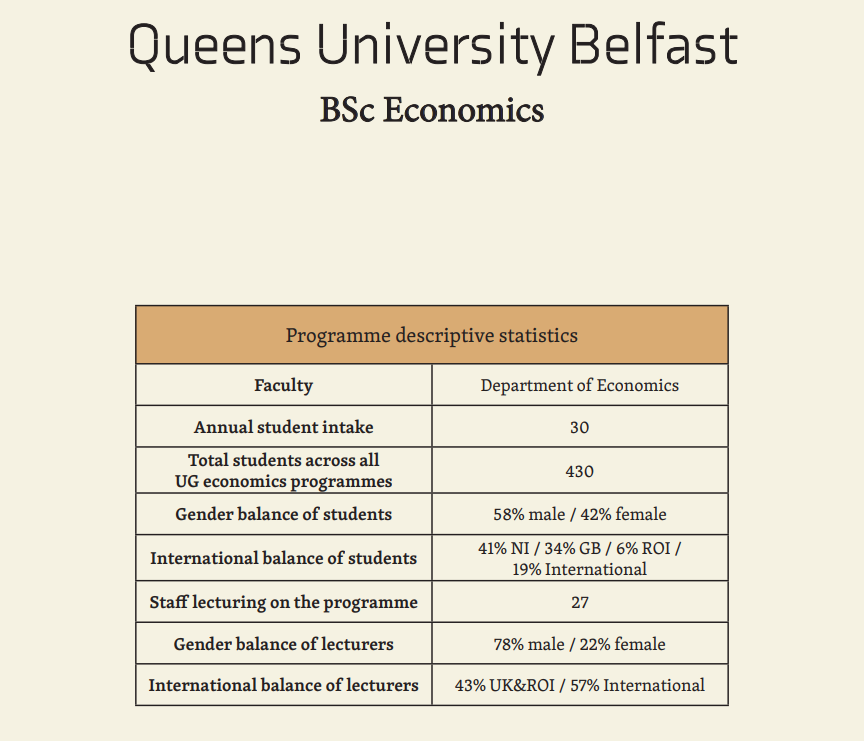

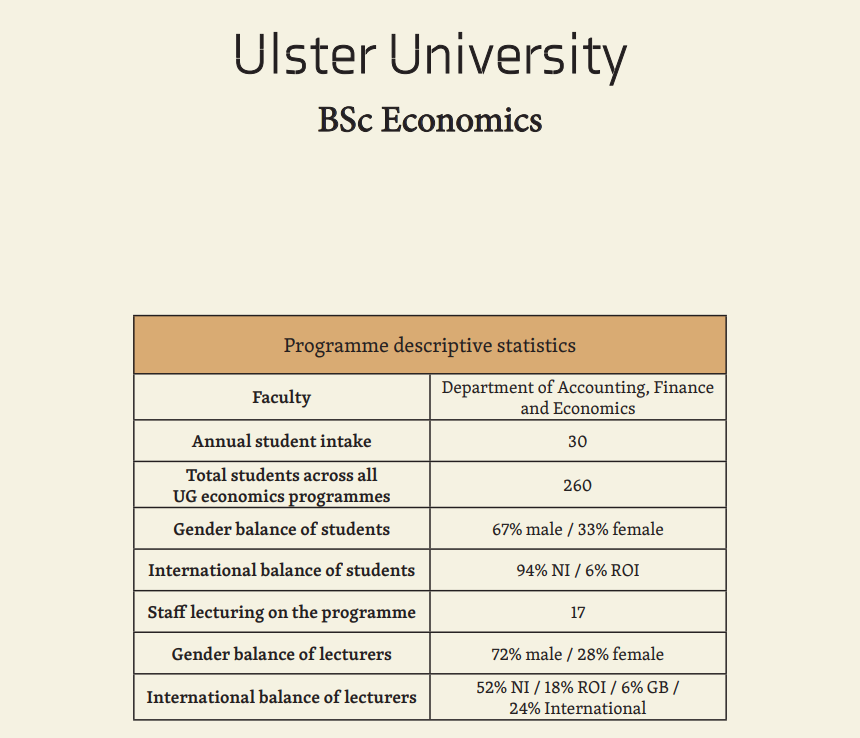

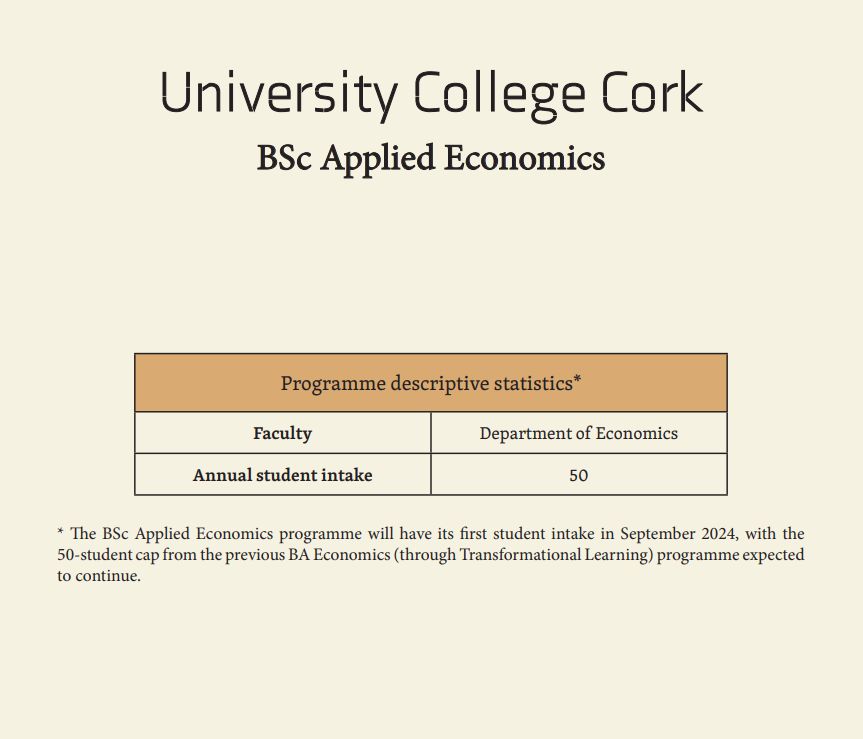

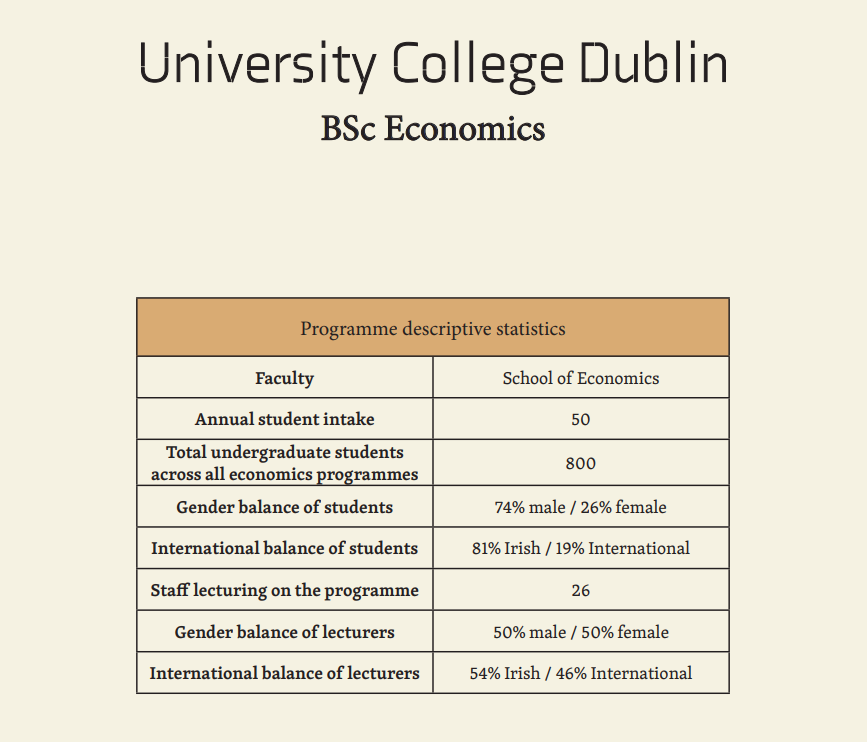

We identified 10 universities on the island of Ireland that teach economics at an undergraduate level: Dublin City University (DCU), Maynooth University (MU), Queen’s University Belfast (QUB), Technological University Dublin (TUD), Trinity College Dublin (TCD), University College Cork (UCC), University College Dublin (UCD), University of Galway (UG), University of Limerick (UL), University of Ulster (UU). We reached out to every department to arrange interviews and received replies from every university except TUD.

Interviews were conducted with the nine remaining departments (in almost every case with the Head of Department and/or the Programme Director of the primary economics undergraduate programme) in October 2023. The purpose of these interviews was to give educators the opportunity to explain their programmes in their own words, as well as to ask about information that is difficult or impossible to obtain externally, such as the internal support provided to teaching staff, changes that have been made to the programme over recent years, and aggregated demographic data on staff and students. Thank you to Robert Gillanders at DCU, Aedín Doris at MU, Heather Dickey, Sonali Sen Gupta and Chris Colvin at QUB, Paul Scanlon at TCD, Ella Kavanagh and Daniel Blackshields at UCC, Kevin Denny and Orla Doyle at UCD, Aidan Kane and Brendan Kennelly at UG, Stephen Kinsella at UL, and Mark Bailey, Áine Doran and Karen Bonner at UU for their participation in interviews.

We then selected a single programme at each university to investigate in depth. We chose the programmes that devoted the most module credits to Economics, which in many cases was not the programme with the most students enrolled. The most common example was selecting the BSc Economics programme over the Bachelor of Arts (Major in Economics) programme. We have noted in the chapters where this is the case.

Each of the modules within the selected programme was then examined through the online module descriptions, including both mandatory and elective modules. The only modules in the programme that we did not investigate were those from outside of the economics department that students could choose from a long or open-ended list of modules, such as in Joint Honours programmes. In some cases the module descriptions were brief or missing, so we contacted the department again to ask for more extensive descriptions, and these were kindly provided by DCU, QUB, UCC and UU.

These public and private materials were examined to determine what topics are covered by the module and roughly how much teaching time is devoted to each of those topics. This was then written up into a first draft and circulated back to our interviewees to ask whether there had been any misunderstandings. Where educators asserted the module covers topics that we could not observe in the module descriptions accessed online or provided to us, we asked for proof that a topic was covered to maintain the integrity of the report. DCU, MU, QUB, TCD, UCC, UL and UU all responded to the draft that we circulated to them, UCD withdrew their involvement in the report, and we did not receive a response from UG.

We did not have the opportunity to observe any teaching ourselves, nor to investigate teaching materials such as lecture slides in depth. We are therefore not making any judgement on the quality of teaching on the programmes at any of the departments contained within this report. We also note that each university has its own unique approach to module descriptions, with varying depths of information provided on topics, perspectives and skills. We have done our best to mitigate any impact on our results through conducting the interviews and feedback rounds described above, but we cannot rule out the possibility that there is still some bias towards programmes and modules with more detailed module descriptions in our report.

We would also repeat that our analysis is not perfect; we have done our best with the materials available to us, but without observing every class for every module in every programme, there will always be details that we might misunderstand or misrepresent. We have minimised this risk by deliberately restricting our analysis to what is most easily observable through module descriptions and interviews, and by providing an overview of what is taught rather than an exhaustive list.

Programme chapters

These chapters contain our analysis of the content of the primary undergraduate economics programme at nine of the ten universities that teach economics on the island of Ireland. We have organised our analysis across 10 categories and 70 subcategories, on which more details can be found here.

Summary and recommendations

You can read more about the unique strengths and limitations of each programme in the chapters linked above, in the following section we will generalise across the programmes.

Every programme centres the Neoclassical and New Keynesian schools of thought in their mandatory modules. Much use is made of marginalist economic models in microeconomics modules, studying individual decision-makers such as consumers or firms and calculating their optimal outcome based on their preferences and budget constraints. Macroeconomic models of non-financial economies often look very similar to the marginalist microeconomic modules, with singular agents representing larger groups. Models such as IS-LM are used to illustrate money markets and interest rates. Many programmes complement these perspectives with insights that have entered the mainstream of economics research over the past two decades – particularly Behavioural economics in microeconomics and New Institutional economics in macroeconomics.

These models are almost always applied to a range of constructed and real-world examples of markets to illustrate the core ideas embedded within the models, and to help students understand the economy and some of the most pressing economic challenges that our societies currently face. Most of the programmes also devote significant attention to training students in the analysis of quantitative data using statistical and econometric methods, equipping them with tools that they can use to better understand economies, sectors and societal challenges.

Although the focus of our analysis is on the specific content of economics undergraduate programmes, we have also been able to develop an understanding of the teaching culture in the departments we have studied. It is noticeable that more weight is placed on teaching by senior staff in departments across Ireland than is typical in European universities, where research concerns generally dominate.

All of the programmes that we have analysed have changed to some extent over the past five years, with a number of departments investing significant time and effort into overhauling and improving their offerings. The direction of travel is clear; towards a broadening of perspectives and methods, an increasing focus on applications and real-world knowledge, and a strengthening engagement with the pressing challenges that our societies face. We see all three of these strands of progress as positive changes, and we hope that this report can spark discussions and provide supportive materials to help Irish economics education improve even further. To this end, we have collected recommendations for potential future changes that could be made to programmes in Ireland, organised along the same categories as our programme chapters.

Despite significant constraints on the time and resources of both staff and students, we see many positives in every programme that we examined. We know that many lecturers in Ireland (and of course beyond) have some frustrations about their own teaching and its context, whether in terms of time available, competing responsibilities and/or textbooks, and that’s why we offer our support in terms of teaching materials and tools for educators, and through our workshops, training sessions and consultancy work. You can contact us at economy.studies@ourneweconomy.nl.

Real-world knowledge and institutions

Economies are open systems of resource extraction, production, distribution, consumption and waste disposal through which societies provision themselves to sustain life and enhance its quality. Due to their complex nature and substantial size, it is impossible to directly observe every aspect of an economy. However, we can certainly study some of its most notable features such as the dominant institutions, actors and processes. The programmes in our report tend to heavily favour teaching students general economic understanding (through models) rather than teaching them specific economic understanding (through case studies and empirics).

To clarify, we consider “real-world knowledge” to be the results of studying specific aspects of the economy as they exist in the real world. For example, real-world knowledge about central banking would be learning about the history of a particular crisis and a central bank’s response to that crisis, the internal institutional structure, the practical mechanisms through which interest rates are manipulated, the data available on financial institutions to their supervisors or their track record of economic forecasting. Whilst the presentation of examples within the context of an economic model can be a valuable teaching tool, we do not consider it to be real-world knowledge as the focus is on the model not the real-world, and because the messiness of reality needs to be trimmed off to fit into the model.

We do observe a handful of modules across every programme that do teach valuable idiographic knowledge about economies and sectors. Economies in the real world are much messier than models, and throw up many challenges and questions that students would not encounter in a purely theoretical module. We strongly believe that students need to understand both theoretical frameworks and the nuances of specific economies and sectors to be able to effectively apply theories to economic problems.

We were alarmed to only find evidence of the money creation process being described accurately to students in two out of nine programmes. Physical money (notes and coins) is created by government agencies and central banks, but the digital money in our economies is created when commercial banks make loans. This money did not exist before it was lent; contrary to the standard textbook explanation of money creation, banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds. The ECB, Bank of England and other central banks do not control the money supply by setting the reserve ratio and the quantity of reserves available; reserves are issued whenever they are demanded (subject to collateral requirements), similar to the reactive supply of physical cash.

Economic theories

Neoclassical and New Keynesian approaches feature heavily in the mandatory modules of almost every programme, and these theoretical lenses are also used to study a wide range of topics in elective modules. Most programmes also expose their students to a range of valuable insights from schools of thought that are less traditionally included in undergraduate economics education, particularly Behavioural and/or New Institutional economics.

We argue that economists gain a better understanding of any given economic phenomenon or topic when they are able to combine multiple theoretical perspectives to understand it, and that students should therefore be taught theories from a wider range of schools of thought. Economists often talk about providing students with a “toolkit” for understanding the economy with their undergraduate education, and it seems clear to us that having a wider range of tools in that toolkit would be beneficial. We would therefore advocate that programmes continue to move towards pluralism, educating their students in more of the rich diversity of available perspectives on economics.

Ways of organising the economy

Market mechanisms dominate the study of provisioning systems across every programme, with private firms often presented as the default producers of goods and services. Some programmes also investigate the public provision of services in a single module. Whilst markets are undoubtedly important features of our economies, in reality, all economies contain a multitude of different microeconomic mechanisms to allocate resources and produce goods and services. For example, healthcare is often provided by a public body, childcare is often provided by (primarily female) family or community members, and financial services are often provided by private firms. Only in the last of those cases is a market involved, and we argue that students need to learn about a wider range of economic mechanisms to have a strong understanding of the economy.

At the macro level, we see vast diversity in political-economic systems globally. Programmes that do not show students different varieties of capitalism risk leaving them with the false impression that there is only one way to organise an economy.

Reflective skills and knowledge

Roughly half of the programmes we examined teach their students about the history of economic thought, and roughly half investigate economic methodology and/or the philosophy of science in at least one module. We believe that both the history of economic thought (and methods) and the philosophy of economics provide vital context to the rest of the economics programme; explaining how our understanding of the economy has changed over time, and how we can learn more about the economy.

Empirical research

The aspect of empirical research that receives the most attention in every programme is the analysis of quantitative data using statistical and econometric techniques. Whilst this is undoubtedly valuable, training students in a broader range of empirical methods (including qualitative methods) would prepare them to be more effective as economists, making the best use of the diversity of data sources available to them in their future careers. Some programmes complement the material on analytical techniques with a thorough explanation of how that quantitative data is collected, and training in data visualisation and communication of results. We see this as essential knowledge for budding economists, and would encourage departments to consider devoting more time to how data is collected and presented.

Qualitative methods allow economists to ask important “why” and “how” questions about the economy using rich non-numeric data; instead of the important “what” and “how much” questions that we can use quantitative methods to study. These approaches are highly complementary, contributing knowledge that is difficult or impossible to obtain using only one type of analysis.

Normative economics

Most programmes have at least one module which engages with some of the ethical questions in economics, but it is rare for engagement in normative economics to be deeper or broader than this. We argue that this apparent reluctance to engage with the normative aspects of economics does not produce value-neutral “positive” economists, because values and value judgements are thoroughly embedded in economics.

Recognising the value judgements that have been made in the course of economic analysis – and defending them cogently – makes economic analysis more scientific, not less. Economists who can comfortably communicate the normative features embedded in their analysis are also more valuable advisors to their employers and society at large. Economists are often advising decision-makers, and it is essential that those decision-makers are made aware of what their economists have and have not assumed or considered in reaching their conclusions.

Giving students space to explore a variety of visions for the economy and what “economic success” means to them can also be an effective route into teaching reflective skills and knowledge, as well as being an inspiring and engaging way to start introductory modules.

Societal challenges

A huge range of societal challenges are presented across (and within) the various programmes – particularly in elective modules. Every programme investigates at least six distinct economic challenges faced by our societies, with allocative efficiency, long-term economic growth and short-term economic fluctuations are by far the most likely to feature in both mandatory and elective modules. Other challenges outside of those three are fairly unlikely to feature heavily in mandatory modules, but we think there would be great value in doing so.

Placing economics and economies in the context of the challenges that we face can provide motivation for students; showing them why economics matters and how the economy can contribute positively to society. Analysing problems and constructing solutions is also a core part of the job description for many economists, whether they’re working in the public, private or third sector; their education should provide them with the skills and knowledge they need for those roles.

Ecological sustainability

Ecological sustainability is perhaps the most pressing problem our societies are currently facing, and the economy has played – and will continue to play – a huge role in both causing ecological crises and responding to them. Most programmes have at least one elective module which investigates these challenges, but we would argue that this challenge is important enough to merit substantial attention in mandatory modules, and no programme that we examined currently provides this.

We would also argue that ecological sustainability cannot be properly understood without concepts deriving from systems thinking and Ecological economics such as embeddedness, planetary boundaries and tipping points. Although externalities can be a useful framing in some contexts, modules that exclusively use this framing risk presenting ecological crises as being much more linear, certain and individualised than they really are.

Inequality

Economic research on inequality has expanded rapidly since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, and this is reflected in the teaching of the programmes examined in this report. Every programme teaches about inequality of income within or between countries, and most teach about both. There are also a few elective modules which teach about inequality across characteristics such as gender or race.

We would argue that both global inequality and wealth inequality within countries deserve more attention than they receive in most programmes, but the most pressing problem from our perspective is the lack of attention paid to the impact that colonialism, slavery and imperialism have had on global and national inequality. We do not think you can understand current wealth inequality within Ireland, the relatively late industrialisation of much of Ireland in historical terms, the current income inequality between Ireland and other countries, or many other important questions without an understanding of how imperialism shaped economic development in Ireland and abroad.

Interdisciplinarity

Most programmes feature very strong representation of other disciplines. A number of the programmes we examined are interdisciplinary programmes by nature (such as Joint Honours degrees), but even Single Honours Economics programmes make use of at least one economic subfield (such as economic geography or political economy), some business studies (such as finance or management) and one other discipline (such as mathematics or philosophy). We think other disciplines and subfields have many valuable perspectives that will improve students’ understanding of the economy, and encourage programmes to make further use of them.

Category descriptions

We have organised our analysis across 10 categories and 70 subcategories, covering allocation mechanisms, schools of thought, specific economies and sectors, empirical tools, societal challenges, and contributions to economics from other disciplines and subdisciplines. You can find more details about each category and subcategory here.